Barbara A. Lewis is a national award-winning author and educator who teaches kids how to think and solve real problems. When she taught at Jackson Elementary School in Salt Lake City, Utah, her students initiated the cleanup of hazardous waste, improved sidewalks, planted thousands of trees, and fought crime. They instigated and pushed through several state laws and an amendment to a national law, garnering 10 national awards, including two President’s Environmental Youth Awards. They also were recognized in the Congressional Record three times. Barbara’s expertise includes:

Barbara A. Lewis is a national award-winning author and educator who teaches kids how to think and solve real problems. When she taught at Jackson Elementary School in Salt Lake City, Utah, her students initiated the cleanup of hazardous waste, improved sidewalks, planted thousands of trees, and fought crime. They instigated and pushed through several state laws and an amendment to a national law, garnering 10 national awards, including two President’s Environmental Youth Awards. They also were recognized in the Congressional Record three times. Barbara’s expertise includes:

- Service learning and social action

- Character education

- Gifted and talented education

She is also available as a keynote speaker and workshop host. Barbara has been featured in/on many national newspapers, magazines, and news programs, including Newsweek, The Wall Street Journal, Family Circle, “CBS This Morning,” “CBS World News,” and CNN. She has also written many articles and short stories for national magazines and has received nine state and national awards for teaching. Her books for Free Spirit Publishing have won Parenting’s ReadingMagic Award and been named “Best of the Best for Children” by the American Library Association, among other honors and awards. She and her husband, Lawrence, live in Park City, Utah, among a forest of shy deer and bossy moose. They have four wonderful children and ten perfect grandchildren.

Another community problem solving project lead my students to plant hundreds of trees across the state. Again calling on the help of the state legislature, they established a fund for children across the state to plant trees— resulting in thousands of new tree plantings. Working with Senator Orrin Hatch, the children succeeded at getting the American the Beautiful Act amended so that kids all over the United States could apply for beautification grants in their states.

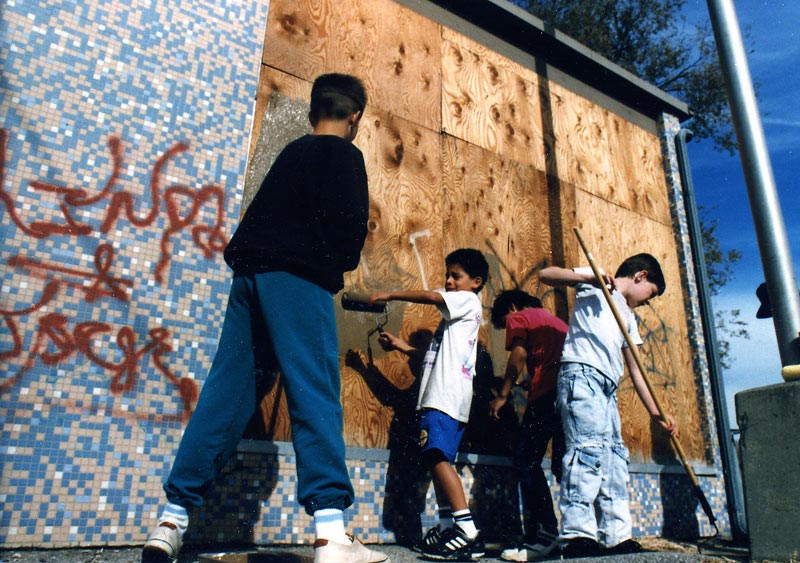

Many of my students had been chased by gangsters welding knives, and some of them and their family members had been shot at with guns. Interested in fighting crime in their area, the students also supported three tough anticrime laws that sailed through the legislature with their help. They placed a crime clue box in the school media center—where students or their parents could place anonymous clues to crimes. The principal solved at least three small crimes from those clues, including stopping a gang fight and identifying the person who had secretly painted graffiti on the walls of the school. The students established a hotline for abused kids and distributed 5,000 stickers with the phone number to students in Salt Lake City School District. Brainstorming additional projects, they produced anti-child-abuse slogans, which were aired on television. One was reproduced on a billboard near their school, with one student’s slogan, “You always lose if you choose to abuse.” Other anticrime projects included lobbing city officials to clean up a drug house across the street from the school. After it was torn down, the students were allowed to put up a few walls in the new low-cost housing replacement. And with the help of the police, they painted over graffiti in the area and put up drug-free school zone signs around the school.

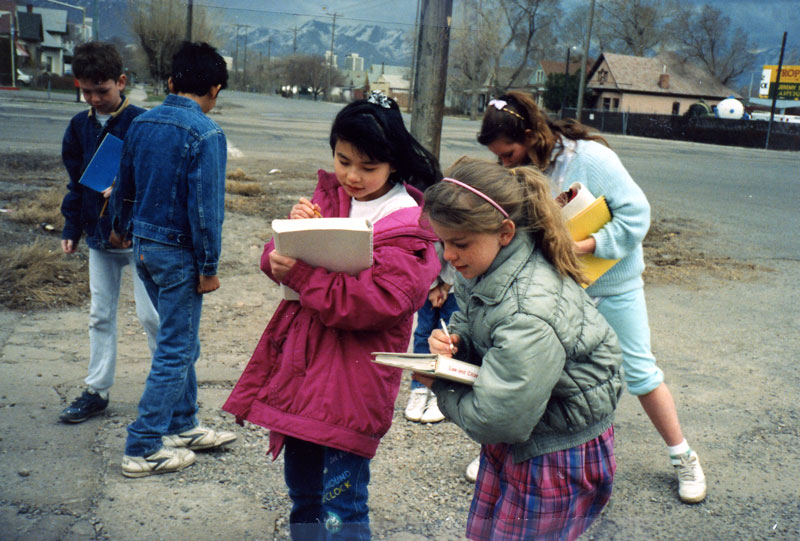

A few years later, we moved to Park City, where I began the gifted program in that school district. Naturally I introduced community problem solving as one of the many components of the program. Students put up flashing school zone signs placed near their school. Other students raised money for Swaner Park. Others conducted a survey on the causes of violence among students and presented it to the State Legislature, while others developed a Website for student votes during a national election. One of the greatest rewards for this type of problem solving is that as students reach out to reduce and solve problems in their areas, the whole process rolls back to them, and they learn self-confidence, a feeling of empowerment, and a better ability to control their own lives.

I skipped kindergarten—not because I was exceptionally bright. I didn’t “skip” to a higher grade. I just refused to go, and my mother didn’t make me. I believe the principal of the school was appalled at my mother’s decision. However, what they didn’t know was that I had a much superior education that year in my basement with my sister, where we held our own school. She was four years old, smarter, and wiser than I was, and because of her superior experience, she insisted on always being the teacher. I sat cross-legged on the floor among the other stuffed animals and doll students and was required to answer all my sister teacher’s questions. She taught me the sounds of vowels and consonants so that I could sound out words. At this time in education, teachers only taught “sight” vocabulary, which meant that you learned the word simply through repetition of seeing it. Thankfully, it was a theory that was soon discarded because the children taught by sight vocabulary lacked word-attack skills. When I entered first grade already reading—due to my secret knowledge of vowels and consonant sounds—my teacher wanted to know how I learned without the benefit of a formal kindergarten instruction. Upon hearing of our basement school, the principal pulled my sister from her fifth grade class to the faculty meeting to demonstrate for teachers how she had taught me to read so well. And I’ve continued reading ever since—although without the companionship of the stuffed animals and dolls.

My sister and I had great imaginations. We spent a lot of time together when we were little and grew fascinated with making up stories. Together we created imaginary people, games, and finally an entire high school of characters. I drew all the paper doll girls, because I could draw better than my sister could. She designed all the boys, who resembled teddy bears. We went so far as to create diaries for some of our favorite characters. I suspect our imaginary tales could have competed as preteen soap operas. With this rich environment for our imaginations, I developed a desire to write. I first tried out poetry. But I received a blow in fifth grade that caused me to discard poetry as a source of expression. I wrote a poem that my teacher accused me of copying from a book—right in front of my class. It devastated me with embarrassment. Her accusation hurt so deeply that I was afraid to write poetry or stories for several years. My love again surfaced as a teen as I began writing my personal history—which was private and safe, and no one could read it. I wrote a few articles and stories while our own children were young, one which won a short story contest, and a children’s novel that won a second place in our state contest. But I really began writing books as a result of my experiences teaching school. I taught in a program for academically talented students that allowed freedom in instruction. I wondered one day why most of what I taught did not really connect to real life. So I began to teach the students to solve real community problems that they identified. With each new experience, I found myself dropping notes inside files, and soon discovered that these notes were leading to possible chapters—which resulted in the publication of my first book, The Kid’s Guide to Social Action.

My sister and I had great imaginations. We spent a lot of time together when we were little and grew fascinated with making up stories. Together we created imaginary people, games, and finally an entire high school of characters. I drew all the paper doll girls, because I could draw better than my sister could. She designed all the boys, who resembled teddy bears. We went so far as to create diaries for some of our favorite characters. I suspect our imaginary tales could have competed as preteen soap operas. With this rich environment for our imaginations, I developed a desire to write. I first tried out poetry. But I received a blow in fifth grade that caused me to discard poetry as a source of expression. I wrote a poem that my teacher accused me of copying from a book—right in front of my class. It devastated me with embarrassment. Her accusation hurt so deeply that I was afraid to write poetry or stories for several years. My love again surfaced as a teen as I began writing my personal history—which was private and safe, and no one could read it. I wrote a few articles and stories while our own children were young, one which won a short story contest, and a children’s novel that won a second place in our state contest. But I really began writing books as a result of my experiences teaching school. I taught in a program for academically talented students that allowed freedom in instruction. I wondered one day why most of what I taught did not really connect to real life. So I began to teach the students to solve real community problems that they identified. With each new experience, I found myself dropping notes inside files, and soon discovered that these notes were leading to possible chapters—which resulted in the publication of my first book, The Kid’s Guide to Social Action.  My father chose my name, Barbara, after the old English ballad, “The Ballad of Barbara Allen.” As a teen I thought that was quite romantic, until I read the ballad and learned that Barbara Allen was a hardhearted, heartbreaking woman—which I did not want to be. In despair, I researched the origin of my name in encyclopedias, hoping for a lovely definition, such as “grace” or “courage.” To my utter horror, I discovered that the origin of my name meant “wild barbarian.” It wasn’t until I taught fifth grade that I received a more satisfactory association for my name. My students called me Barbie Doll. Now, I found my name association with a doll to be far more flattering than a heartbreaking woman or a wild barbarian. Even though I bear no resemblance to this exaggerated doll, I felt the meaning of my name was finally vindicated.

My father chose my name, Barbara, after the old English ballad, “The Ballad of Barbara Allen.” As a teen I thought that was quite romantic, until I read the ballad and learned that Barbara Allen was a hardhearted, heartbreaking woman—which I did not want to be. In despair, I researched the origin of my name in encyclopedias, hoping for a lovely definition, such as “grace” or “courage.” To my utter horror, I discovered that the origin of my name meant “wild barbarian.” It wasn’t until I taught fifth grade that I received a more satisfactory association for my name. My students called me Barbie Doll. Now, I found my name association with a doll to be far more flattering than a heartbreaking woman or a wild barbarian. Even though I bear no resemblance to this exaggerated doll, I felt the meaning of my name was finally vindicated.